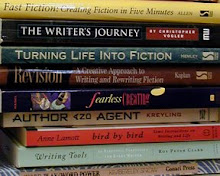

Book

writers must create writing that pulls a reader in, that engages us so

well, we can't stop reading. A favorite nonfiction writer, Malcolm

Gladwell, spoke about this task--and its challenge to most writers--in

the preface to his book What the Dog Saw and Other Adventures.

Gladwell's topics are potentially dry. I love his ability to present his material in an amazingly engaging way.

"Good

writing does not succeed or fail on the strength of its ability to

persuade," he said. "It succeeds or fails on the strength of its

ability to engage you, to make you think, to give you a glimpse into

someone else's head--even if in the end you conclude that someone else's

head is not a place you'd really like to be."

Each

book writer has their topic, the thing they must write about. Some

write about a fantasy world, some write flowers, some write about

growing up with addictions. No matter your topic, the trick is to make

it engaging. It's harder than it sounds.

The key is something called "container."

This

week I'm gathering some new material for my fall online class, Strange

Alchemy, which begins October 25 and focuses writers on container in

their story. What is present, now, and how can it be enhanced? How

does container intersect with character--so that you understand a

character better by the setting that echoes their motivations or

emotions? How does an event come alive in a perfectly depicted

container?

If you have any doubt about the importance of container, think of films. Imagine The Matrix being shot on a farm in rural New Zealand. Or that classic, West Side Story,

taking place on a ranch in Kansas. Container may be something you

completely overlook as you draft your story, or it might be your

favorite aspect. Not enough container means your reader won't engage

emotionally with the characters or events--because (and here's the

kicker) container is the main vehicle for delivering emotion and meaning

in story.

This is the first step to producing the engaging writing that Gladwell is talking about.

Tough Material, Great Container

In my Strange Alchemy class, we read an essay by Susan J. Miller, excerpted from her book Never Let Me Down.

Miller's father was a well-respected jazz musician who hung out with

the likes of George Handy and Stan Getz. But he was also a heroin

addict, and her life was terribly affected by this. Her memoir is

heart-breaking.

Some

writers are repulsed by such a topic, others feel it's terribly

pertinent to today's world. We always have a lively debate, trying to

understand why the essay affects us so much, and in the end, we usually realize it is because of Miller's extraordinary "container," the living environment of her story.

This

is the key to engaging writing. Container, the larger environment of

your book's story, delivers more emotion than plot, characters, topic,

structure, or all of these combined. "It's

counter-intuitive," is the comment I get most often--"you would think

that good plot, exciting action, would create emotional response."

Good

plot creates momentum, yes. It drives the story forward. But it's

container that brings forth that emotional response. It's what makes

us feel hit in the gut by a story's tender moment or feel our hearts

racing with anticipation by a twist. Without container, plot is just a

series of events, like a newspaper report.

Why

else would I, as a reader, become so engaged in the healing of a

crime-ridden neighborhood, the comeback of Hush Puppy Shoes, and other

examples from Gladwell's classic book, The Tipping Point? I

don't care about Hush Puppies. Really. But I did when he talked about

them. Same with Susan Miller's work. Heroin addiction is not on my

list of fun things to read about. But I was totally engrossed by her

tale.

Because both Gladwell and Miller are masters of writing container.

How Is Container Presented?

Container is presented in writing in several ways. Here are a few from just one paragraph of Miller's essay:

1. physical setting (being on a speeding subway train, watching the night flash by outside the grimy windows)

2. use of the five senses (screech of train wheels, whisper of her father's voice against her ear)

3. physical sensations (the rocking of a train causing nausea, felt in the body)

4. word choice ("screech" and "whisper" echo the sounds of jazz being played--Miller's overall container for the essay)

5.

paragraph length and flow (a series of clauses, separated by commas,

giving the impression of movement and jerkiness while on the subway

train)

The

effect of this paragraph--one where her father takes her on a train

ride then gleefully whispers that he just dropped acid--is one of

terror. A young girl is aware that her father might at any moment decide

the train car is a tomb and try to jump off. What can she do? Not

much. She just has to ride out the ride.

It's an astonishing container.

This Week's Exercise

Choose

a dead spot in your writing--a paragraph or a page. Insert one of the

above tools to increase container. See if you can let go of your

preferences as a writer and be willing to see your work from the

reader's view. Does more emotion come through?

No comments:

Post a Comment